About 40 years ago, the French narratologist Gérard Genette introduced the term seuils—French for thresholds, translated into English as paratexts—to describe the many ancillary texts that may accompany a book’s publication, from cover images to authorial prefaces to reviews. Authors, publishers, printers, patrons, readers, and others involved in the making and reception of books have long been familiar with paratexts, especially in the early modern period, when printed books often appeared with complex configurations of prefaces, epistles to readers, appeals to patrons, errata sheets, and printed commentaries. By giving a single name to this category of texts, and by broadening it to include independently circulating materials such as author interviews and critical reviews, Genette (and his English translator, Jane E. Lewin) gave us a word to conjure with.

Today, the term paratext has travelled beyond literary studies and book history into fields that study other kinds of media, including film and television studies (see Jonathan Gray’s Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts; NYU Press, 2010), and videogame studies via Mia Conalvo’s Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Video Games (MIT Press, 2007) and Steven E. Jones’s The Meaning of Video Games: Gaming and Textual Strategies (Routledge, 2008). The concept of paratext has proven especially fruitful for understanding videogames, as Jan Švelch has recently demonstrated in a survey of the term’s takeup by the field.

My own contribution to this conversation among fields has taken the form of a recent special issue for the journal Games and Culture, on the topic “Video Games and Paratextuality”:

- Alan Galey, “Introduction: Reconsidering Paratext as a Received Concept”

- Regina Seiwald, “Beyond the Game Itself: the Paratextuality of Video Games”

- Jon Saklofske, “To the Center of Nowhere: Deep Mapping Digital Games’ Paratextual Geographies”

- Alan Galey, “Behind the Scenes at ApertureScience.com: Portal and Its Paratexts”

- Steven E. Jones, “Response: In and Out of the Game, as Usual”

(Most of the articles are available open access via the journal directly, but in a couple of cases I’ve linked to versions on the authors’ institutional repositories. Unfortunately the journal made an error and published some of these articles in different issues; see the individual articles linked from this page for the correct citation details.)

This special issue grew out of a panel I organized for the 2021 conference of the Canadian Game Studies Association. Our collaboration, however, began a year earlier in 2020, partly as a way to maintain connections with colleagues during the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in its early months. As with many pandemic projects, it took some time to finish the articles, and there were disruptions along the way, but I am very happy about the connections we made. Each of the contributions shows how concepts of textual scholarship translate to the study of videogames, but also how videogames require us to modify, rethink, and sometimes abandon ideas that may be too book-centric in their original framing. In my introduction I wrestled with Genette’s Eurocentric and presentist biases in particular, but we all drew inspiration from Steve’s 2008 book The Meaning of Video Games, which helpfully conceives of videogames as texts, in the broadest sense of that term, and not merely as analogues or competitors for books. (Though there’s definitely a need for work on relationships between books and videogames, including books in videogames; see this recent article on “High Fantasy RPGs and the Materiality of the Medieval Book” by Bard Swallow, one of my students in the Book History and Print Culture program, also in Games and Culture.)

My own article focuses on an especially weird and fun paratext for the classic videogame Portal, a first-person platform/puzzle-solving game set in the fictional Aperture Science Laboratories. In this game, the player must navigate their way through an underground research facility that is strangely empty of other humans, accompanied only by the voice of GLaDOS, a passive-aggressive rogue AI fixated on carrying out Aperture Science’s research program even after some hinted-at global catastrophe—which ties into the Half-Life games from the same publisher, Valve. As I unpack in the article, Aperture Science is a finely tuned satire of postwar big-science research, with GLaDOS as its insane AI genuis loci (written by Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek, and voiced by Ellen McLain in one of the greatest videogame voice-acting performances of all time, which continues in Portal 2).

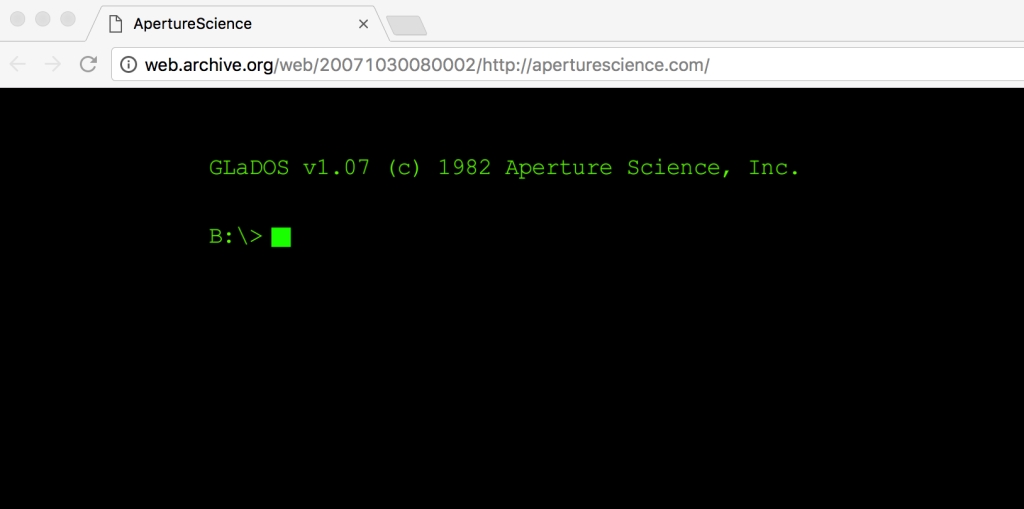

The paratext I take as a case study is the tie-in website ApertureScience.com, launched in 2006 to promote the game:

As you can see in this screenshot, this isn’t your typical promotional website. ApertureScience.com used Flash to simulate a blinking cursor and command prompt in the style of the DOS operating system (hence GLaDOS’s name), and visitors could enter commands once they logged into the system. For many videogame players of my generation, a blinking green (or maybe amber) command line was how we first learned to interact with computer systems, and it remains a visual trope in depictions of computing today. ApertureScience.com simulated the experience of using one of the lab’s own computers, which ran the GLaDOS operating system (apparently v1.07 from 1982), and allowed users to explore files, discover secrets, and even fill out a very strange application questionnaire if they could work out the right commands.

You may have noticed my use of past tense in the paragraph above. ApertureScience.com’s command-line simulation was implemented in Flash, which means the site ceased to work in most web browsers after 2021. Even before then, however, ApertureScience.com had been updated a few times, and the command prompt was replaced with a Christmas-themed video in 2010. For many years, the only way to access the earlier, interactive versions of ApertureScience.com was via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. (There was a period after 2021 when the site wouldn’t work on the Wayback Machine either, but it works now.) The site’s history has been thoroughly documented on the Half-Life wiki on Fandom.com, and I’ll return to the question of ApertureScience.com as an artifact of internet history below.

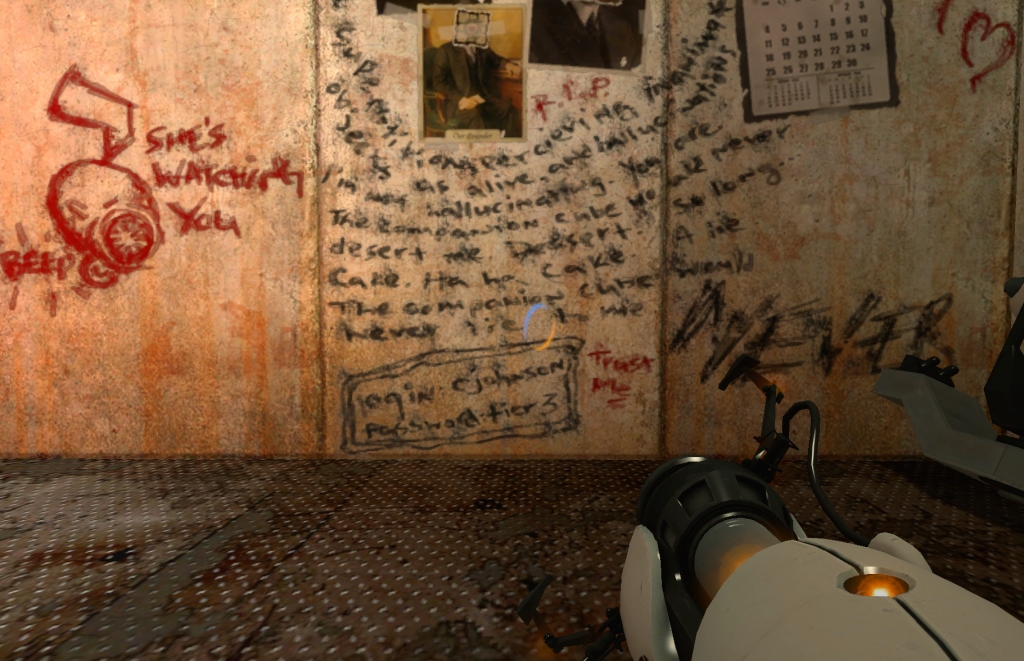

But before I say any more about how we access this videogame paratext, there’s the bigger question of why? As I explain in my article, ApertureScience.com is an in-universe paratext for Portal, meaning that it adds to Portal‘s story and fleshes out its world. Works of fanfiction do this all the time, but ApertureScience.com is not fanfiction; it was created by Valve and the game’s writers, and is considered part of Portal‘s canon. One can play Portal the videogame without experiencing the website—in any of its multiple versions—but canonical paratexts like this raise intriguing questions about where Portal‘s edges as a creative work begin and end. For example, in the game itself, one may do some optional exploring and discover these login credentials written on a wall in a supposedly inaccessible part of the research facility:

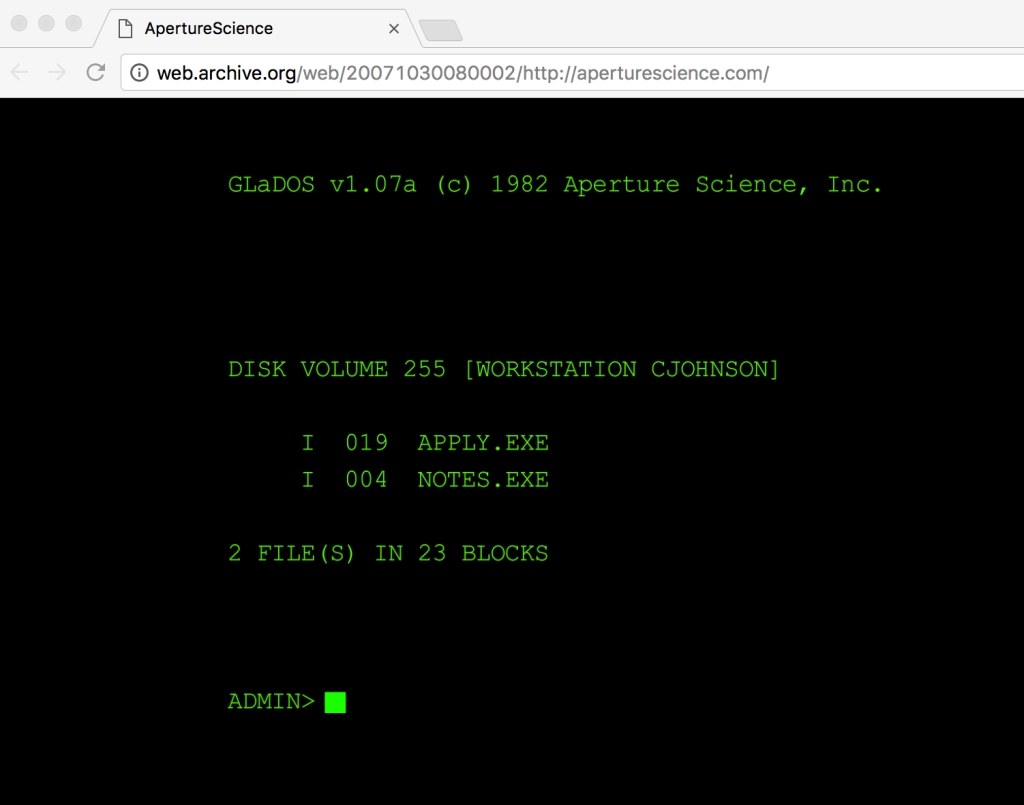

The login name “cjohnson” and password “tier3” next to the words “trust me” can be used at ApertureScience.com to log in as Aperture Science’s eccentric founder, Cave Johnson (who appears as a character in the 2011 sequel, Portal 2, voiced to perfection by the actor J.K. Simmons). Players who never discover this easter egg can still log in using any username and the easily guessable password “portal” or “portals,” and can open the “apply.exe” file to fill out the bizarre application form—itself a subtle world-building text which tells the reader as much about the organization asking the questions as it does about anything else. But logging in to ApertureScience.com as Cave Johnson gives us access to a second, secret file:

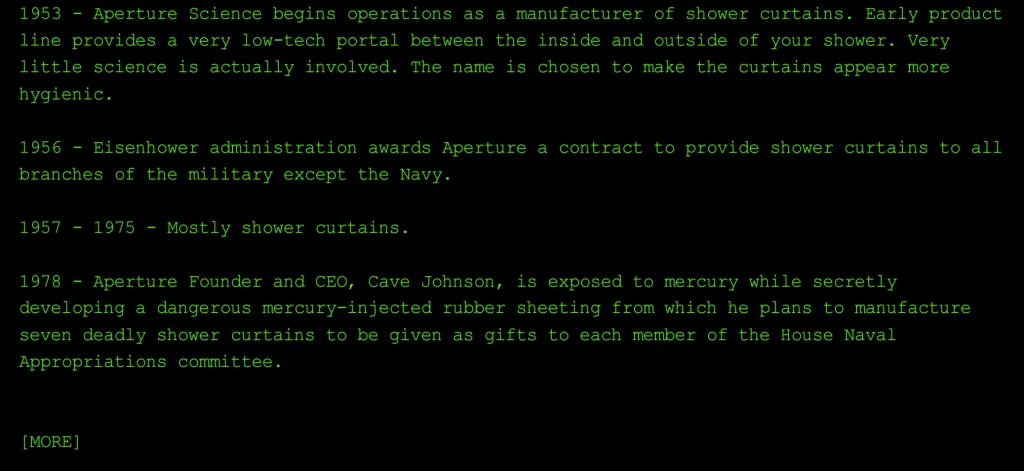

Opening the “notes.exe” file from the list above grants access to a brief historical timeline of Aperture Science Laboratories, leading up to the events that initiate Portal. The whole thing is a fun read; here’s just the first screen:

Like most easter eggs, all of this material is deliberately hard to access, but rewarding for diligent players once they find it. What I like most about this easter egg, however, is not only the background and nuance it adds to an intentionally minimalist story, but also the fact that ApertureScience.com is a distinct digital artifact in its own right while also part of Portal as a creative work that spans multiple artifacts—not to mention multiple versions, which is one of the preoccupations of textual scholarship no matter the form of the text in question, whether manuscript, print, born-digital, or otherwise. What do paratexts like ApertureScience.com mean for the study of videogames as cultural texts and historical artifacts, and for their preservation, archiving, and interpretation in the future? These are questions I consider in my article, and which my co-contributors to the special issue, Regina, Jon, and Steve, unpack along with questions of their own as well.

As I suggest in the article—building on a line of inquiry I’ve pursued in an earlier article on The Tragically Hip and pro-am music archiving—we can learn much about these questions from the work of dedicated fan communities and the resources they create, like the entry for ApertureScience.com on the Half-Life Fandom.com wiki. As I was working on this article, a similar fan-driven project at the Valve Archive was creating an emulated version of ApertureScience.com (in all four of its distinct versions) so that players could have access to this otherwise ephemeral part of videogame history. If you’re intrigued by the description of ApertureScience.com above and in my article, I recommend checking out their version—armed with the secret commands documented on the wiki.

Now that the Valve Archive has created what amounts to a facsimile of the original site, my next project may take the form of a scholarly critical edition of ApertureScience.com—i.e. an accessible version which includes commentary to help the reader, indicates of the variants between the versions, and an analysis of the original Flash code for the site. My PhD student Ellen Forget and I have begun work on this, using the Twine platform, and I’ll post an update down the road.

You must be logged in to post a comment.